By Mary Hartley, RD, with Dana Shultz

All of the diet and health advice we’re fed today can be confusing. But some have suggested that what it really all comes down to is eating the right amount of calories and staying active most days of the week. While this may sound like a simple solution, ‘how many calories we really need’ can be rather elusive.

There’s a whole slough of online tools that promise to accurately calculate the amount of calories we require. But how many of us really know if we’re ‘moderately active’ or ‘vigorously active?’ What’s the difference between the two. And are we also to assume that all women 5’5” tall and 130 pounds have the same resting metabolic rate?

To answer these sometimes baffling questions, DietsInReview.com’s Registered Dietitian, Mary Hartley, RD, weighs in to help us find the truth about what we really need to know when it comes to calorie requirements.

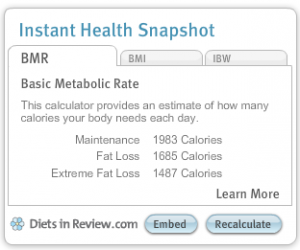

According to Mary, the online calorie calculators use a formula to find the basal metabolic rate (BMR) or resting metabolic rate (RMR), and then they apply an activity factor to determine the total daily energy expenditure (calories).

The formulas that predict BMR are the Harris Benedict Equation and the Mifflin-St. Jeor formula. Both take into account height, weight, age, and gender. The Mifflin-St. Jeor formula is slightly more accurate, but both create errors by failing to adjust for individual differences in metabolically-active lean body mass vs. fat mass. Calories may be underestimated for adults with more lean body mass and overestimated for folks with more fat. The formulas work best for Caucasian males and worse for African Americans, women and the elderly.

To further complicate the prediction, says Mary, an “activity factor” must be applied – either sedentary, very light, light, moderate, or exceptionally active. There is much subjectivity and very little guidance involved here. But based on the activity level assigned, a factor is added to the BMR to calculate total calorie requirement. For instance, BMR x 1.2 is for sedentary, BMR x 1.55 is for moderately active, and BMR x 1.9 is for Michael Phelps. When weight loss is the goal, calories are subtracted from the total to produce a loss of about 2 pounds per week.

To further complicate the prediction, says Mary, an “activity factor” must be applied – either sedentary, very light, light, moderate, or exceptionally active. There is much subjectivity and very little guidance involved here. But based on the activity level assigned, a factor is added to the BMR to calculate total calorie requirement. For instance, BMR x 1.2 is for sedentary, BMR x 1.55 is for moderately active, and BMR x 1.9 is for Michael Phelps. When weight loss is the goal, calories are subtracted from the total to produce a loss of about 2 pounds per week.

The better way to assess calorie requirements, however, is to have your metabolic rate measured by a process called “Indirect Calorimetry” that calculates your calorie burn rate by measuring your oxygen uptake. It’s a standard procedure that has been around for many years. The test measures the calories you burn at rest and then estimates the calories you burn performing ADLs (Activities of Daily Living), such as dressing and eating, and PA (Physical Activity), your exercise and physical labor. Calorie requirements are the total of the three numbers.

The ADLs and PA are subjective again, but for more people, the BMR/RMR makes up 75-80 percent of the calories they burn. To improve the accuracy of the test, it’s suggested to fast for 12 hours, abstain from exercise for 48 hours, and be tested in a quiet room three separate times and then take the average of those three measurements. There is often disagreement between the formulas and Indirect Calorimetry. Read about Mary’s experience in this blog post, Adventures in Metabolic Testing.

The test is not covered by insurance, takes about 10-12 minutes and prints out a report to reveal your individual calorie requirements. As far as cost goes, it varies for each individual testing facility, but will likely set you back about $100. But you can contact your local university or hospital to see if they offer the testing and how much they charge. Sometimes colleges offer students or alumni discounts.

But the bottom line, as Mary reminds us, is that most people don’t need as much food as our skewed reference points tell us, which is a good thing because in olden times, there was a lot of physical activity but not a lot of food. In short, if you can’t afford or don’t have access to Indirect Calorimetry testing, use the online tools to get a basic idea of your caloric needs and go from there.

Mary suggests strengthening the “activity factor” of the test by keeping a record of your every physical activity (including inactivity) performed in 24 hours. Do this for as many days as you can and take an average to find the calories you actually burn in one day. Then plug this figure into the online tool to estimate your caloric needs.

But no matter how close you get to an accurate figure, calorie counting is an imprecise science at best. That’s why it’s better to focus on eating lots of low calorie vegetables, staying active, and limiting the act of eating to when you are actually hungry. If you find yourself gaining or losing weight, make adjustments as needed.

Also Read: